During school visits, I often ask kids to think of ways to find facts for writing nonfiction. Then we make a list of different sources from reliable Internet sites and nonfiction books to museums, magazines and TV documentaries or The History Channel.

To gather information for The First Step, I used all these resources and more. I read many books about Boston in the 1840s, the Roberts family and their case. I also learned a lot from primary sources, documents and artifacts created at the time these events took place. Here are some examples of how these primary sources helped me:

Small details mean a lot. In the afterword of The First Step, I mention that very little is known about Sarah Roberts. That’s a problem when you’re writing a book about someone. How do you make readers feel connected to Sarah and her story?

E. B. Lewis’s beautiful art is a big part of it. You’ll notice that he puts Sarah in the center of the story by having her on every page he could. Instead of playing “Where’s Waldo?” you can go through our book and find fourteen pictures of Sarah.

As an author, I tried to paint word pictures of Sarah’s world. At the beginning of the story, for example, I say that Sarah was lucky her school was so close to her home. Then I show that by writing, “Sarah dashed past the hay sellers and carpenters, the organ makers and oystermen. After crossing Causeway Street, she was just steps from the Otis School.” Can you see that picture in your mind? Does it seem as if Sarah has an easy trip to make every day to her school?

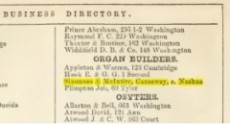

I knew Sarah lived on Andover Street and the school was Lancaster Street, so I knew her route. But how did I know what stores she passed?

On the left, you can see a picture of Causeway Street today. This spot, where the Boston Bruins and the Boston Celtic sport teams play, is very close to where Sarah Roberts lived. Clearly none of those 1840s businesses or buildings still exist. I couldn’t find old photos or paintings of them, either. Luckily insurance companies made maps of the buildings on Boston streets, reporting each one’s address and what it was made of. With my buildings’ addresses in hand, I could scour the 1849 Boston Directory for the listings of businesses on

On the left, you can see a picture of Causeway Street today. This spot, where the Boston Bruins and the Boston Celtic sport teams play, is very close to where Sarah Roberts lived. Clearly none of those 1840s businesses or buildings still exist. I couldn’t find old photos or paintings of them, either. Luckily insurance companies made maps of the buildings on Boston streets, reporting each one’s address and what it was made of. With my buildings’ addresses in hand, I could scour the 1849 Boston Directory for the listings of businesses on  Causeway Street.

Causeway Street.

I did a lot of work so find those the hay sellers and carpenters, the organ makers and oystermen. I think it was worth it. Then readers could compare Sarah’s short journey to the one the city want to force her to make because she was African American. Naming a business like a hay seller also gives readers a picture of what life back then was like.

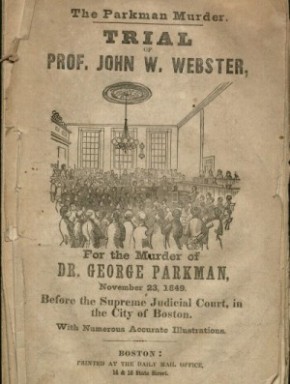

A picture is worth a thousand words (sometimes!). Sarah’s trial is an important part of this story. I read Charles Sumner’s amazing speech (see below) over and over so I could imagine him saying it. But what about the room he was speaking in?  What did that courtroom look like? I knew illustrator E. B. Lewis would want to know, but I did too. It’s easier to write about something you can actually imagine.

What did that courtroom look like? I knew illustrator E. B. Lewis would want to know, but I did too. It’s easier to write about something you can actually imagine.

Sadly for us, the courtroom doesn’t exist anymore. Many photographs of its famous Judge Lemuel Shaw were taken, but none in his courtroom.

photographs of its famous Judge Lemuel Shaw were taken, but none in his courtroom.

Then I found out about a gruesome murder trial that was going on right about the same time as Sarah’s. Everyone in Boston and the rest of the country were glued to their newspapers for updates. Luckily for me, Judge Shaw was hearing the case in his courtroom. In those days, newspapers were illustrated by drawings. I looked up stories about the Parkman murder—and there was Sarah’s courtroom.

Another mystery solved!

Words matter. It’s tough to read the amazing speech Charles Sumner made to argue Sarah’s case. It’s long, and Sumner’s sentences are written in an old-fashioned style that  can be hard to understand.

can be hard to understand.

Some of the words he used sound racist today, but they were considered much more respectful in that era. Sumner was a devoted champion of equal rights. His moral and legal ideas about why African Americans deserved total equality were so strong that they convinced Abraham Lincoln, and influenced Earl Warren, the Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, as he explained why segregated schools were against the law in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

I only had room for a few of Sumner’s lines in The First Step. It was hard to choose which of his points to use. If you stick with reading Sumner’s argument, perhaps you’ll find some that you like, too.